Coronavirus

Technology Solutions

December 7, 2020

Don’t Confuse Medical with Public Health

Guidance

Mask and Filter Protection are Part of a Swiss Cheese Defense Program

Clean Air is the Goal for Hotels and Cruise

Lines

__________________________________________________________________________

Don’t Confuse Medical with Public Health

Guidance

Michael Mina

of Harvard says it is

important

to distinguish medical from public

health guidance. This is good

advice. In fact it is important to also

distinguish guidance for vaccine manufacture.

It is also desirable to distinguish between sub

segments. The guidance for personnel entering an

isolation unit are far different than for a

person at the registration desk in a hospital.

|

Application |

Filtration Efficiency % |

|

Medical |

|

|

Registration |

90 |

|

Non infectious |

95 |

|

Infectious |

99.99 |

|

Pharmacy |

99.99 |

|

Vaccine Mfg. |

|

|

Fill and finish |

99.999 |

|

Adjacencies |

99.9 |

|

Public High Positivity Zone |

|

|

Open Parks |

60 |

|

City Streets |

90 |

|

Elevators |

95 |

|

Subways |

99 |

The efficiency needs can be achieved with a

combination of filters and masks. If there are

filter cubes on the city streets at

intersections the need for more efficient masks

is less. If the elevator has a HEPA filter and

laminar air flow there is less of a burden on

the mask. This combination of filters can be

conceived as the swiss cheese defense program as

explained below.

Mask and Filter Protection are Part of a Swiss

Cheese Defense Program

This concept was the basis of an article by Siobhan

Roberts

published Dec. 5, 2020

in the NY Times.

Lately, in the ongoing

conversation about how to defeat the coronavirus,

experts have made reference to the “Swiss cheese

model” of pandemic defense.

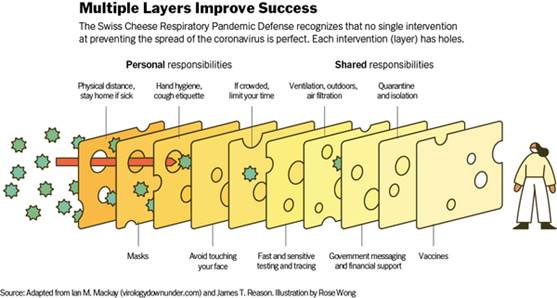

The metaphor is easy enough to grasp: Multiple layers of protection, imagined as cheese slices, block the spread of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. No one layer is perfect; each has holes, and when the holes align, the risk of infection increases. But several layers combined — social distancing, plus masks, plus hand-washing, plus testing and tracing, plus ventilation, plus government messaging — significantly reduce the overall risk. Vaccination will add one more protective layer.

“Pretty soon you’ve created an impenetrable

barrier, and you really can quench the

transmission of the virus,” said Dr. Julie

Gerberding, executive vice president and chief

patient officer at Merck, who recently

referenced the Swiss cheese model when speaking

at a virtual gala fund-raiser for MoMath, the

National Museum of Mathematics in Manhattan.

“But it requires all of those things, not just

one of those things,” she added. “I think that’s

what our population is having trouble getting

their head around. We want to believe that there

is going to come this magic day when suddenly

300 million doses of vaccine will be available

and we can go back to work and things will

return to normal. That is absolutely not going

to happen fast.”

Rather, Dr. Gerberding said in a follow-up

email, expect to see “a gradual improvement in

protection, first among the highest need groups,

and then more gradually among the rest of us.”

Until vaccines are widely available and taken,

she said, “we will need to continue masks and

other common-sense measures to protect ourselves

and others.”

In October, Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at

the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health,

retweeted an infographic rendering

of the Swiss cheese model, noting that it

included “things

that are personal *and* collective

responsibility — note the ‘misinformation mouse’

busy eating new holes for the virus to pass

through.”

“One

of the first principles of pandemic response is,

or ought to be, clear and consistent messaging

from trusted sources,” Dr. Hanage said in an

email. “Unfortunately the independence of

established authorities like the C.D.C. has been

called into question, and trust needs to be

rebuilt as a matter of urgency.” A catchy

infographic is a powerful message, he said, but

ultimately requires higher-level support.

The Swiss cheese concept originated with James

T. Reason, a cognitive psychologist, now a

professor emeritus at the University of

Manchester, England, in his 1990 book, “Human

Error.”

A succession of disasters including

the Challenger shuttle explosion, Bhopal and

Chernobyl — motivated the concept, and it became

known as the “Swiss cheese model of accidents,”

with the holes in the cheese slices

representing errors that

accumulate and lead to adverse events.

The model has been widely used by safety

analysts in various industries, including

medicine and aviation, for many years. (Dr.

Reason did not devise the “Swiss cheese” label;

that is attributed to Rob Lee, an Australian

air-safety expert, in the 1990s.) The model

became famous, but it was not accepted

uncritically; Dr. Reason himself noted that it

had limitations and was intended as a generic

tool or guide. In 2004, at a workshop addressing

an aviation accident two years earlier near

Überlingen, Germany, he delivered a talk with

the title, “Überlingen: Is Swiss cheese past

its sell-by date?”

In 2006, a review of the model, published by

the Eurocontrol

Experimental Center, recounted that Dr.

Reason, while writing the book chapter “Latent

errors and system disasters,” in which an early

version of the model appears, was guided by two

notions: “the biological or medical metaphor of

pathogens, and the central role played by

defenses, barriers, controls and safeguards

(analogous to the body’s autoimmune system).”

The cheese metaphor now pairs fairly well with

the coronavirus pandemic. Ian M. Mackay, a

virologist at the University of Queensland, in

Brisbane, Australia, saw a smaller version on Twitter,

but thought that it could do with more slices,

more information. He created, with

collaborators, the “Swiss

Cheese Respiratory Pandemic Defense” and

engaged his Twitter community, asking for

feedback and putting the visualization through

many iterations. “Community engagement is very

high!” he said. Now circulating widely, the

infographic has been translated into

more than two dozen languages.

“This multilayered approach

to reducing risk is used in many industries,

especially those where failure could be

catastrophic,” Dr. Mackay said, via email.

“Death is catastrophic to families, and for

loved ones, so I thought Professor Reason’s

approach fit in very well during the circulation

of a brand-new, occasionally hidden, sometimes

severe and occasionally deadly respiratory

virus.”

The following is an edited version of a recent

email conversation with Dr. Mackay by the

Washington Post.

Q. What does the Swiss cheese model show?

A. The real power of this infographic — and

James Reason’s approach to account for human

fallibility — is that it’s not really about any

single layer of protection or the order of them,

but about the additive success of using multiple

layers, or cheese slices. Each slice has holes

or failings, and those holes can change in

number and size and location, depending on how

we behave in response to each intervention.

Take masks as one example of a layer. Any mask

will reduce the risk that you will unknowingly

infect those around you, or that you will inhale

enough virus to become infected. But it will be

less effective at protecting you and others if

it doesn’t fit well, if you wear it below your

nose, if it’s only a single piece of cloth, if

the cloth is a loose weave, if it has an

unfiltered valve, if you don’t dispose of it

properly, if you don’t wash it, or if you don’t

sanitize your hands after you touch it. Each of

these are examples of a hole. And that’s in just

one layer.

To be as safe as possible, and to keep those

around you safe, it’s important to use more

slices to prevent those volatile holes from

aligning and letting virus through.

Q. What have we learned since March?

A. Distance is the most effective intervention;

the virus doesn’t have legs, so if you are

physically distant from people, you avoid direct

contact and droplets. Then you have to consider

inside spaces, which are especially in play

during winter or in hotter countries during

summer: the bus, the gym, the office, the bar or

the restaurant. That’s because we know

SARS-CoV-2 can remain infectious in aerosols

(small floaty droplets) and we know that aerosol

spread explains Covid-19 superspreading events.

Try not to be in those spaces with others, but

if you have to be, minimize your time there

(work from home if you can) and wear a mask.

Don’t go grocery shopping as often. Hold off on

going out, parties, gatherings. You can do these

things later.

Q. Where does the “misinformation mouse” fit in?

A. The misinformation mouse can erode any of

those layers. People who are uncertain about an

intervention may be swayed by a loud and

confident-sounding voice proclaiming that a

particular layer is ineffective. Usually, that

voice is not an expert on the subject at all.

When you look to the experts — usually to your

local public health authorities or the World

Health Organization — you’ll find reliable

information.

An effect doesn’t have to be perfect to reduce

your risk and the risk to those around you. We

need to remember that we’re all part of a

society, and if we each do our part, we can keep

each other safer, which pays off for us as well.

Another example: We look both ways for oncoming

traffic before crossing a road. This reduces our

risk of being hit by a car but doesn’t reduce it

to zero. A speeding car could still come out of

nowhere. But if we also cross with the lights,

and keep looking as we walk, and don’t stare at

our phone, we drastically reduce our risk of

being hit.

We’re already used to doing that. When we listen

to the loud nonexperts who have no experience in

protecting our health and safety, we are

inviting them to have an impact in our lives.

That’s not a risk we should take. We just need

to get used to these new risk-reduction steps

for today’s new risk — a respiratory virus

pandemic, instead of a car.

Q. What is our individual responsibility?

A. We each need to do our part: stay apart from

others, wear a mask when we can’t, think about

our surroundings, for example. But we can also

expect our leadership to be working to create

the circumstances for us to be safe — like

regulations about the air exchange inside public

spaces, creating quarantine and isolation

premises, communicating specifically with us

(not just at us), limiting border travel,

pushing us to keep getting our health checks,

and providing mental health or financial support

for those who suffer or can’t get paid while in

a lockdown.

Q. How can we make the model stick?

A. We each use these approaches in everyday

life. But for the pandemic, this all feels new

and like a lot of extra work. Because everything

is new. In the end, though, we’re just forming

new habits. Like navigating our latest phone’s

operating system or learning how to play that

new console game I got for my birthday. It might

take some time to get across it all, but it’s

worthwhile. In working together to reduce the

risk of infection, we can save lives and improve

health.

And as a bonus, the multilayered risk reduction

approach can even decrease the number of times

we get the flu or a bad chest cold. Also,

sometimes slices sit under a mandate — it’s

important we also abide by those rules and do

what the experts think we should. They’re

looking out for our health.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/05/health/coronavirus-swiss-cheese-infection-mackay.html

Clean Air is the Goal for

Hotels and Cruise Lines

Elaine Glusac covered the activities in this

travel segment in an article in the NY Times

published Dec.

3, 2020.

Her article shows that while HEPA filters

and other reliable air cleaning devices are

being used there is very likely false optimism

about other technologies.

When the coronavirus first

hit, hotels quickly adopted enhanced cleaning

polices, including germ-killing electrostatic

spraying and ultraviolet light exposure in guest

rooms and public areas.

But as research on virus

spread has shifted focus from surface contact

to airborne

transmission, some hotels and cruise

ships are scrubbing the very air travelers

breathe with a variety of air filtration and

treatment systems.

“The best amenity that any

hotel could provide under those circumstances is

safety, especially in the air,” said Carlos

Sarmiento, the general manager of the Hotel

Paso del Norte in El Paso, Texas. The

1912 vintage hotel recently reopened after a

four-year renovation that included installing a

new air purification system called Plasma Air

that emits charged ions intended to neutralize

the virus and make particles easier to filter

out.

With the new air-scrubbing

campaigns, hotels are following airlines, many

of which have hospital-grade, high-efficiency

particulate air (HEPA) filters that are said to

be over 99 percent effective in capturing tiny

virus particles, including the coronavirus.

Hotels and cruise ships can

more easily ensure social distancing than

airplanes, but, given the recent research on the

importance of enhanced air filtration, some are

adding air-cleaning dimensions to their heating,

ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems,

which already aim to remove dust, smoke, odors

and allergens.

Researchers, including those

at New Orleans’s Tulane University, have

found that the tiny aerosol particles

of SARS-CoV-2 that are emitted when someone with

the virus speaks or breathes can remain in the

air for up to 16 hours.

Along with social distancing,

mask wearing is the first line of defense

against breathing contaminated air indoors, said

Dr. Philip M. Tierno Jr., a professor of

microbiology and pathology at New York

University School of Medicine, who has consulted

with HVAC companies.

“HVAC systems are of great

significance in reducing the amount of airborne

particles since this virus can be spread in an

airborne fashion,” he added, calling the tiniest

aerosols “the most dangerous.”

Air cleaning technologies include bipolar

ionization systems, which, according to their

manufacturers, send charged ions out on air

currents that damage the surface of the virus

and inactivate it. They may also bind with the

virus aerosols, causing them to fall or be more

easily filtered out.

However, some experts are skeptical,

pointing to evidence that these systems may

introduce ozone or particles that are dangerous

if inhaled. ASHRAE,

a professional society of air-conditioning,

heating and refrigerating engineers, notes that

the technology is still “emerging” and lacks

“scientifically-rigorous, peer-reviewed

studies.” The bipolar ionization company

AtmosAir Solutions provided results of tests

performed by the independent Microchem

Laboratory, which evaluates sanitizing products,

that found the technology reduced the presence

of coronavirus by more than 99 percent within 30

minutes of exposure.

“We talk about it as nature’s cleaning device,”

said Kevin Devlin, the chief executive of

WellAir, which sells the bipolar ionization

system Plasma Air installed at the Hotel Paso

del Norte. He noted that air at high elevations

in the mountains that “smells clean” has higher

amounts of ions.

Some anti-viral HVAC systems feature germicidal

ultraviolet light in the ductwork (the Food and

Drug Administration states that

ultraviolet-C lamps have been shown to

inactivate the virus). Such a system was

installed at The

Distillery Inn in Carbondale, Colo., and

includes a three-hour disinfection cycle between

guests.

Systems often use a combination of these

technologies with efficient air filters that

remove contaminants. Filters with Minimum

Efficiency Reporting Values (MERV) of 13 or

higher are best at capturing the coronavirus,

according to the Environmental

Protection Agency.

According to its website,

the agency “recommends increasing ventilation

with outdoor air and air filtration as important

components of a larger strategy that includes

social distancing, wearing cloth face coverings

or masks, surface cleaning and disinfecting,

handwashing, and other precautions.”

“In a transient environment, like a hotel, motel

or dormitory, you don’t know who was there

before you and what their health was,” said Wes

Davis, the director of technical services with

the Air Conditioning Contractors of America, a

trade association, adding that good housekeeping

is a top priority in such places. “As for the

other items like ultraviolet exposure or

ionization, every little bit helps, but I’m not

quite sure any of them is the perfect solution.

It’s more like a concert.”

Throughout the summer, the Madison

Beach Hotel, part of Hilton’s Curio

Collection of hotels, in Madison, Conn., used

its outdoor spaces for dining and even holding

meetings in tents. But with the approach of cold

weather, HVAC contractors installed an air

purification system that uses UV light and

ionized hydrogen peroxide in most public areas

of the hotel, including the indoor restaurant

and meeting rooms. Spa treatment rooms each have

their own portable air purification systems.

“We wanted to create an environment that was as

safe as possible,” said John Mathers, the

hotel’s general manager, adding that each guest

room has its own closed HVAC system that doesn’t

mingle with others and thus doesn't require

extra purifying. “The air being recirculated in

your room is your air.”

But many hotels are bringing units into the

guest rooms for extra assurance. In Rhode

Island, rooms at the Weekapaug

Inn and Ocean

House hotel, both run by Ocean House

Management, have Molekule air

purifiers that destroy pollutants and viruses at

a rate above 99 percent, according to

the independent testing group Aerosol

Research and Engineering Laboratories.

Larger units were recently added to restaurants

and public spaces, and the portable units have

become a top seller, starting at around $500, in

Ocean House’s gift shop.

Decisions about installing air purification

systems tend to happen at the property or

ownership level, rather than the brand level.

But Hilton has AtmosAir’s bipolar ionization air

purification systems in its Five

Feet to Fitness rooms, more than 100

guest rooms across 35 hotels that double as mini

gyms with weights, indoor cycles and meditation

chairs.

Many hotels have long offered allergy-free or

wellness rooms to travelers that feature

heightened purification systems. Pure Wellness

has its Pure

Room technology that claims to eliminate

viruses, bacteria and fungi, including air filters effective

enough to trap the coronavirus, in over 10,000

rooms worldwide.

The 112-passenger SeaDream I from the SeaDream

Yacht Club took many precautions —

including pre-embarkation Covid-19 testing,

electrostatic fogging of public areas and UV

light sterilization after nightly turndown —

before it launched its winter season from

Barbados on Nov. 7, and still a passenger got

the virus within days of departure, cutting

the trip short. Eventually nine

infections were diagnosed and the line canceled

future 2020 sailings. (The cruise line did not

respond to a requests for comment on whether any

improvement had been made to the ship’s

ventilation system.)

SeaDream’s failed cruise exemplifies the

challenges the entire industry faces. Some

health experts think that upgraded air

filtration could help. Adopting systems that are

“aimed at reducing occupant exposure to

infectious droplets/aerosols,” and upgrading

HVAC systems with MERV 13 filters were among 74

critical recommendations to

ship lines made by the Healthy Sail Panel, a

group of public health experts assembled by

Royal Caribbean Group and Norwegian Cruise Line

Holdings in September.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintains that

ships remain vulnerable to spreading infection

based on population density and the inability of

crew in particular to maintain social distance

in their work spaces and living quarters. Still,

cruising is expected to resume in U.S. waters

for ships carrying 250 or more passengers and

crew in the first half of 2021, pending

certification under the C.D.C.’s Framework

for Conditional Sailing Order,

which spells out minimum standards for social

distancing, face coverings and hand hygiene, but

does not mention air circulation systems.

Despite the C.D.C.’s lack of emphasis on air

filtration, some cruise companies are upgrading

their ventilation systems, in addition to

designating quarantine areas and reconfiguring

dining rooms.

Norwegian Cruise Line,

for example, has announced its ships will use

HEPA filters. And Princess

Cruises has said it will upgrade its

ships’ HVAC systems to MERV 13 filters, refresh

the air in cabins and public spaces every five

to six minutes, and install HEPA filters in

areas such as medical centers and isolation

rooms.

The new Virgin

Voyages cruise line, whose launch has

been delayed by the pandemic, confirmed it had

installed AtmosAir bipolar ionization systems on

its inaugural ship, the roughly 2,700-passenger

Scarlet Lady, and a second ship coming in 2021.

“This

was a multimillion-dollar investment and based

on our research and growing understanding of the

virus, was an important step to sailing safely,”

wrote Tom McAlpin, the chief executive of Virgin

Voyages, in an email.