Coronavirus

Technology Solutions

October 21, 2020

Can Foss Fibers with Sciessent Antimicrobials

Inactivate Virus in Transient Droplets?

Masks for Five Billion People Who Cannot Afford

$100/yr

Avery Dennison uses Adhesives to Insure Tight

Fit for Masks

Vogmask has an Efficient, Comfortable Tight

Fitting Mask

Transmission from Surfaces is Far Less than from the Air and Efforts are Being Misplaced

______________________________________________________________________________

Can Foss Fibers with Sciessent Antimicrobials

Inactivate Virus in Transient Droplets?

This was the question posed to Bill Cummings of

Foss and Jeff Trogolo of Sciessent in a

telephone discussion yesterday. It follows an

article we wrote in the October 13 Alert.

In the telephone call we pursued the

potential for ions to move through a transient

droplet and inactivate virus which might

subsequently be released.

The mechanism was described in the

October 13 Alert.

The question is how far the ions will travel

within the droplet. If it is a 10 micron droplet

will there be inactivation on the periphery 180

degrees from the point of contact? Jeff pointed

out that time is also a factor. A large droplet

takes longer to evaporate, so there is more time

for the ions to work their magic.

If, in fact, virus released from small droplets

formed from

large droplets represent a significant

portion of the total and if the viruses can be

inactivated during the large droplet stay on the

mask, then this procedure is quite important.

Search results for: Sciessent

5 results found.

Sorted by relevance / Sort

by date

1. McIlvaine

Coronavirus Market Alert

... Solutions

October 13, 2020 Can Antimicrobials Penetrate

Droplets and Inactivate Virus? Nextera, Sciessent,

and Foss Partner to Produce Antimicrobial Masks Sciessent Antimicrobial

in Nextera Mask Spectrashield Meets ...

Terms matched: 1 - Score: 61 - 14

Oct 2020 - URL:

http://www.mcilvainecompany.com/coronavirus/subscriber/Alerts/2020-10-13/Alert_20201013.html

2. McIlvaine

Coronavirus Market Alert

... Production

from 17 tons per day in March to 51 tons per day

in December Sciessent Antimicrobial

Used in Hanesbrands Masks Teho Filter Using

Ahlstrom Media for N88 Masks in Finland ...

Terms matched: 1 - Score: 50 - 30

May 2020 - URL:

http://www.mcilvainecompany.com/coronavirus/subscriber/Alerts/2020-05-29/Alert_202005029.html

3. McIlvaine

Coronavirus Market Alert

... Coronavirus

Technology Solutions April 21, 2020 Viroblock

Effective Against Coronavirus Sciessent Antimicrobial

in Nextera Mask Spectrashield Meets Efficiency

Requirements Berry Global has New Material for

Surgical Masks NC State ...

Terms matched: 1 - Score: 41 - 29

Apr 2020 - URL:

http://www.mcilvainecompany.com/coronavirus/subscriber/Alerts/2020-04-21/Alert_20200421.html

4. McIlvaine

Coronavirus Market Alert

... Masks

Tustar Teams with Neatrition to Introduce High

Efficiency Masks to the U.S. Market Sciessent Antimicrobial

Used in Hanesbrands Masks Teho Filter Using

Ahlstrom Media for N88 Masks in Finland ...

Terms matched: 1 - Score: 37 - 10

Jun 2020 - URL:

http://www.mcilvainecompany.com/coronavirus/subscriber/Alerts/2020-06-10/Alert_20200610.html

5. Coronavirus

Alerts Table of Contents

... Haul

October 13, 2020 Can Antimicrobials Penetrate

Droplets and Inactivate Virus? Nextera, Sciessent,

and Foss Partner to Produce Antimicrobial Masks Sciessent Antimicrobial

in Nextera Mask Spectrashield Meets ...

Terms matched: 1 - Score: 25 - 20

Oct 2020 - URL:

http://www.mcilvainecompany.com/coronavirus/subscriber/Alerts/TofC.html

Another important use of the technology is to

extend the life of masks.

The fibers can inactivate virus on the

mask surface. This reduces the frequency

of cleaning.

It is particularly important if

comfortable highly efficient and tight fitting

masks are used. If a $30 mask can be worn 100

times the cost is only 30 cents per wearing. If

500 million people spend $100/yr the cost would

be $50 billion worldwide. Fifty million

Americans would spend $5 billion per year. Larry

Summers, former U.S. secretary and Harvard

economics professor estimates that the pandemic

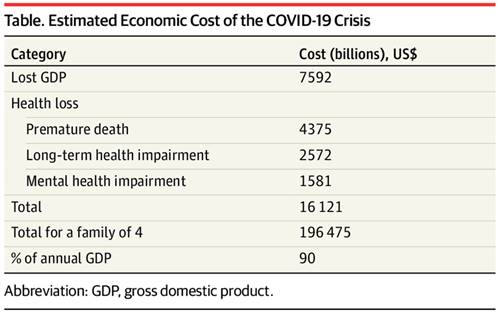

will cost over $16 trillion just in the U.S.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2771764

McIlvaine has added the life quality benefits

and costs to the economic costs. The thrill of

attending a motor cycle or political rally is

weighed against the pain of watching loved ones

suffer or even die. This results in an

additional social cost which is greater than the

economic cost.

The fact that masks can be comfortable or even

attractive is part of the calculation of social

cost . Hoodies have been determined by virtue of

teenage expenditures to have life quality

benefits which exceed the discomfort of wear in

the summer time.

Masks for Five Billion People Who Cannot Afford

$100/yr

For those who can only afford $10/yr for masks,

why not buy a $30 mask and wear it for three

years? It will provide far more protection than

the typical cloth mask which is replaced

frequently. If the mask has anti microbials and

can be occasionally cleaned and if it does not

rely on electrostatic charges for efficiency

then this can be the answer for even the poorest

citizens in Asia and Africa. In fact many of the

poorest people are walking around with Michael

Jordan T shirts why not with sterilized used

masks.

Avery Dennison uses Adhesives to Insure Tight

Fit for Masks

Neal Carty, business director, North America,

and senior director, global R&D, Avery

Dennison Medical,

describes the role of skin-friendly adhesive in

a new type of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator

(FFR).

None of the “Ps” in Personal Protective

Equipment (PPE) are supposed to stand for

“pain,” but unfortunately that is exactly what

some N95 FFRs are causing for many healthcare

professionals. Nurses, physicians and other

providers have reported rashes and other skin

trauma following long wear times in

tight-fitting N95 half-mask FFRs.

As the medical device industry responds to PPE

requirements, and healthcare institutions look

to build up better stockpiles, new approaches to

FFRs promise to offer clinicians greater choice

and comfort. One such development is an N95 FFR

that adheres directly to the user’s face. This

design eliminates the need for elastic bands to

pull the device against the face. Instead, the

respirator conforms to the face of each

individual end user, secured around the nose and

mouth with a skin-friendly adhesive.

This type of N95 FFR, developed by Global Safety

First and produced and distributed to the

healthcare industry by Avery Dennison Medical,

secures to the wearer’s face with a

skin-friendly acrylic adhesive. Avery Dennison

Medical ©

For any N95 FFR to properly protect the wearer,

there can be no leakage around the edge of the

respirator. To be certified by the National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH), these respirators must be proven to

offer protection from particulate materials,

including common bacteria and submicron

particles, with at least 95 percent efficiency.

For a self-adhesive N95 FFR, it is critical for

the adhesive system to provide an effective seal

boundary. The right double-coated adhesive tape

enables this seal integrity. One side of the

tape carries an aggressive adhesive designed to

irreversibly bond to the FFR filtering material,

typically a polypropylene Spunbond Meltblown

Spunbond (SMS) nonwoven. The other side carries

a gentle adhesive designed to adhere the FFR to

the wearer’s skin, where it can remain

comfortably and securely in place for several

hours, if needed.

Of course, with PPE, what goes on must come off.

When the user is finished with the FFR, he or

she must be able to remove it easily, with

minimal discomfort. The skin-facing adhesive

used in the FFR must offer gentle peel adhesion

for atraumatic removal.

In conclusion, the medical device industry is

working to offer healthcare professionals better

PPE options. Skin-friendly adhesives play a key

role in half-mask N95 FFRs that create a

gentle-but-secure protective boundary on the

user’s face.

Vogmask has an Efficient, Comfortable Tight

Fitting Mask

Vogmask has been a leader in masks for air

pollution, wild fires and pollen protection .

McIlvaine contends that masks designed for this

set of contaminants are better suited to the

COVID battle than cloth or surgical masks

The virus is now shown to travel as small

aerosols. It can also attach itself to small

particles.

Keep in mind that the average person

inhales 7.5 million particles as small as 0.1

microns every minute.

Yes, this is every minute not every year.

This is assuming relatively clean air which has

been designated ISO 9. In Mumbai on a bad day or

California when wildfires are burning the

numbers will be much higher. The 0.1 particles

are invisible unless you catch a shaft of

sunlight through your window.

Perfume is mostly particles less than 0.3

microns. So you smell but don’t see it.

Cigarette smoke ranges from 0.1 microns to over

1 micron so some of it is visible but most is

not. This discussion of particle sizes leads to

a conclusion that if you have a mask which does

not protect you from perfume or cigarette smoke

it is not likely to protect you from COVID.

Vogmask has five different sizes and various

other features to provide the tight fit which is

crucial. It has a highly efficient particulate

filter and is comfortable.

The VM filter media in Vogmask has an

obsolescence date three years from manufacture.

Once the middle layer particle filter is

saturated with microscopic particles, there is a

noticeable increase in breathing resistance and

the mask should be replaced. Only in very poor

quality or in proximity to wildfire or other

natural disaster is this likely to occur in as

little as three to five months.

If any part or assembly of the mask is damaged,

or if a good seal is not achievable, discard the

mask. Most Vogmask users replace the Vogmask at

one year of use.

DAILY MAINTENANCE

You may use alcohol wipes >61% or alcohol spray

on surfaces.

Expose to sunlight.

Hand washing: Do not wash the mask frequently.

Excessive washing will eventually affect

filtering efficiency. Do not submerge the

mask. Hand wash rinsing outer and inner layer

with warm water. Add a drop of liquid soap and

gently rub inner and outer layer. Rinse again

and hang to fully dry before storage.

The need to disinfect or clean masks is a

function of the viral load probabilities. If you

are a nurse in a COVID ward the probability is

100% every hour. If you are walking in the woods

with only occasional people passing by the odds

are probably a thousand times less than for the

COVID nurse.

If you are riding the subway in a neighborhood

with a 10% or greater positivity ratio you

probably want to use the alcohol spray or just

rotate masks.

The central thesis in this Alert is that we need

tight fitting efficient and comfortable masks.

The cost is insignificant compared to the

benefits.

Unfortunately few citizens understand the

risks they are taking with loose fitting

inefficient masks. This has to change and when

it does the filtration industry has to be

prepared to meet the needs.

Transmission from Surfaces is Far Less than from

the Air and Efforts are Being Misplaced.

People walking around in cloth masks are

spraying everything in sight but remain at high

risk.

The public over estimates surface risk

and underestimates the airborne risk.

Wired

just had a good summary of what is known about

surface transmission.

A

study on

fomites and Covid-19,

was

released as a preprint in March by researchers

at the University of California, Los Angeles,

the National Institutes of Health, and

Princeton. It was a look at how long the novel

coronavirus lasted on different kinds of

surfaces. At the time, little was known about

how the virus was transmitted, so the question

was important. Depending on the material, the

researchers could still detect the virus after a

few hours on cardboard, and after several days

on plastic and steel. They were careful to say

that their findings only went as far as that.

They were reporting how quickly the virus

decayed in a laboratory setting, not whether it

could still infect a person or was even a likely

mode of transmission.

But in the hazy panic of the time, many people

had already taken up fastidious habits:

quarantining packages at the door, bleaching

boxes of cereal brought back from the store,

wearing hospital booties outdoors. A single set

of research results didn’t start those

behaviors, but—along with other early studies

finding the virus on surfaces in hospital rooms

and on cruise ships—it appeared to provide

validation.

Since March, additional studies have painted a

picture that is much more subtle and less scary.

But like that first study, each can be easily

misinterpreted in isolation. One clear takeaway

is that, given an adequate initial dose, some

amount of the virus can linger for days or even

weeks on some surfaces, like glass and plastic,

in controlled lab conditions. Emphasis on controlled. For

example, earlier this month, an Australian

study published

in Virology

Journal found

traces of the virus on plastic banknotes and

glass 28 days after exposure. The reaction to

that number felt to some like a replay of March:

a single study with a bombshell statistic

sparked new fears about touchscreens and cash.

“To be honest, I thought that we had moved on

from this,” says Anne Wyllie, a microbiologist

at Yale University.

Of course, this was another laboratory study

done with specific intentions. The study was

done in the dark, because sunlight is known to

quickly deactivate the virus, and it involved

maintaining cool, favorable temperatures. Debbie

Eagles, a researcher at Australia’s national

science agency who coauthored the research, says

that taking away those environmental variables

allows researchers to better isolate the effect

of individual factors, like temperature, on

stability. “In most ‘real-world’ situations, we

would expect survival time to be less than in

controlled laboratory settings,” Eagles writes

in an email. She advises handwashing and

cleaning “high-touch” surfaces.

The second consistent finding is that there’s

plenty of evidence of the virus on surfaces in

places where infected people have recently been.

Wherever there has recently been an outbreak,

and in places where people are asked to

quarantine or are treated for Covid-19, “there’s

viral RNA everywhere,” says Chris Mason, a

professor at Weill Cornell Medicine. That makes

going out and swabbing a useful tool for keeping

track of where the virus is spreading.

It’s tempting to piece those two elements

together: If the virus is on the surfaces around

us, and it also lasts for a long time in lab

settings, naturally we should vigorously

disinfect. But that doesn’t necessarily reflect

what’s happening. In a

study published in

September in Clinical Microbiology and

Infection, researchers in Israel tried to

piece it all together. They conducted lab

studies, leaving samples out for days on various

surfaces, and found they could culture the

remaining virus in tissue. In other words, it

remained infectious. Then they gathered samples

from highly contaminated environments: Covid-19

isolation wards at a hospital, and at a hotel

used for people in quarantine. The virus was

abundant. But when they tried to culture those

real-world samples, none were infectious. Later

that month, researchers at an Italian hospital reported

similar conclusions in The

Lancet.

In addition to environmental conditions, a

confounding factor might be saliva, or the stuff

that we often mean when we talk about droplets

sticking onto surfaces. In her own research,

Wyllie has studied how long certain viral

proteins remain intact in saliva to help

determine the reliability of Covid-19 spit

tests. For her purposes, stability is a good

thing. But some proteins have appeared to

denature more quickly than others, she notes,

suggesting the virus as a whole does not remain

intact and infectious. That could be because

saliva tends to be less hospitable to pathogens

than the synthetic substances or blood serums

often used in lab-based stability studies.

Consider, Wyllie says, the extraordinary chain

of events that would need to happen to

successfully spread SARS-CoV-2 on a surface. A

sufficiently large amount of the virus would

need to be sprayed by an infected person onto a

surface. The surface would need to be the right

kind of material, exposed to the right levels of

light, temperature, and humidity so that the

virus does not quickly degrade. Then the virus

would need to be picked up—which you would most

likely do with your hands. But the virus is

vulnerable there. (“Enveloped” viruses like

SARS-CoV-2 do not fare well on porous surfaces

like skin and clothing.) And then it needs to

find a way inside you—usually through your nose

or your eye—in a concentration big enough to get

past your mucosal defenses and establish itself

in your cells. The risk, Wyllie concludes,

is low. “I’ve not once washed my groceries or

disinfected my bags or even thought twice about

my mail,” she says.

Low risk is not, of course, no risk, she adds.

There are high-touch objects that merit

disinfection, and places like hospitals need

clean rooms and furniture. People at high risk

from Covid-19 may want to take extra

precautions. But the best advice for breaking

that object-to-nose chain, according to all the

health experts I spoke with: Wash your hands.