Coronavirus

Technology Solutions

October 12, 2020

The Value of Tight Fitting Effective Masks

Demonstrated by White House Events

Mask Fit is Critical to Success Against COVID

But Most Are Not Aware of This

Glendale Arizona Buying Room Air Purifiers with

HEPA Filters

NYC Indoor Restaurants Reopen with HEPA Filters,

UV and Ionizers

Meat Packers Need Efficient Masks and Fan Filter

Units

________________________________________________________________________

The Value of Tight Fitting Effective Masks

Demonstrated by White House Events

On October 10 there was a rally in the Rose

Garden of the White House. An earlier event

celebrating the Supreme Court nomination will

likely result in 100 new coronavirus infections.

This includes the original 13 directly tied to

the event and then others who will be infected

later by the super spreading. The October 10

event will probably result in 200 infections.

Here is why.

|

Parameters |

Supreme Court Event |

Oct 10 Event |

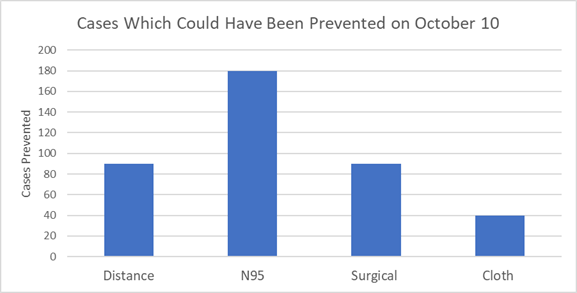

Cases Prevented if Implemented |

|

# of people in attendance |

100 |

400 |

200 Total Preventable |

|

Long Distance Travel |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Social Distancing |

No |

No |

90 |

|

N95 Masks |

No |

No |

180 |

|

Surgical Masks |

No |

|

90 |

|

Cloth Masks |

No |

|

40 |

Many of the people traveled by air to the event.

There was no social distancing. Some people were

unmasked but many had cloth masks. Even if some

were wearing surgical masks they were probably

loose fitting. If everyone had been wearing

efficient tight fitting masks, there may be only

20 cases resulting from the event of which only

four would be directly from the event. If

everyone had been wearing surgical masks with

some effort at obtaining a good fit the cases

would be reduced to 110 and 90 deaths prevented.

If everyone had had a loose fitting cloth mask

probably only 40 cases would have been avoided

and there would still be 160.

This

type of behavior is why as of today the

U.S. has had 8 million cases and 220,000 deaths.

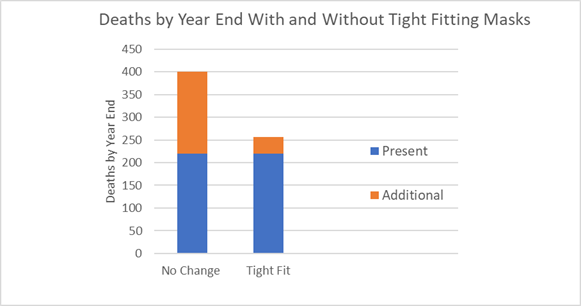

The latest models show that we are headed toward

400,000 deaths by January 1. These additional

180,000 deaths could be reduced by 80% with

proper use of tight fitting N95 masks.

The net benefit to U.S. citizens including both

economic and quality of life will be 180,000 x

$20 million = $3.6 trillion.

This is a net benefit from which an

expenditure of $12 billion for highly efficient

masks is already deducted.

Mask Fit is Critical to Success Against COVID

But Most Are Not Aware of This

A new article in Nature addresses many of

the issues on masks which McIlvaine has been

investigating. However, the problem is the lack

of recognition that a 10 micron droplet

impinging on a mask will evaporate or be

converted into small droplets.

In any case the ultimate salts which

contain the virus will be just a small fraction

of a micron in size. Much of previous mask

efficiency analysis was focused on particles. A

2 micron particle adhering on a mask fiber will

stay there. A droplet will evaporate. So we have

two different situations. Keep in mind that the

sub-micron aerosols or particles will penetrate

in the same way as perfume or smoke.

McIlvaine comments are included in

italics where the information is either

misleading or questionable.

Even well-fitting N95 respirators fall slightly

short of their 95% rating in real-world use,

actually filtering out around 90% of incoming

aerosols down to 0.3 µm. And, according to

unpublished research, N95 masks that don’t have

exhalation valves — which expel unfiltered

exhaled air — block a similar proportion of

outgoing aerosols. Much less is known about

surgical and cloth masks, says Kevin Fennelly, a

pulmonologist at the US National Heart, Lung,

and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

In a review of observational studies, an

international research team estimates that

surgical and comparable cloth masks are 67%

effective in protecting the wearer. This may

be true for 5 micron particles but not 5 micron

droplets which become aerosolized. See the mask

leakage vs particle size in the October 9 Alert.

In unpublished work, Linsey Marr, an

environmental engineer at Virginia Tech in

Blacksburg, and her colleagues found that even a

cotton T-shirt can block half of inhaled

aerosols and almost 80% of exhaled aerosols

measuring 2 µm across. Once you get to aerosols

of 4–5 µm, almost any fabric can block more than

80% in both directions, she says. Same

answer. Initial blockage is only the first

phase.

Multiple layers of fabric, she adds, are

more effective, and the tighter the weave, the

better. Another study found that masks with

layers of different materials — such as cotton

and silk — could catch aerosols more efficiently

than those made from a single material.

Eric Westman, a clinical researcher at Duke

University School of Medicine in Durham, North

Carolina, co-authored an August study that

demonstrated a method for testing mask

effectiveness. His team used lasers and

smartphone cameras to compare how well different

cloth and surgical face coverings stopped

droplets while a person spoke. “I was reassured

that a lot of the masks we use did work,” he

says, referring to the performance of cloth and

surgical masks. But thin polyester-and-spandex

neck gaiters — stretchable scarves that can be

pulled up over the mouth and nose — seemed to

actually reduce the size of droplets being

released. “That could be worse than wearing

nothing at all,” Westman says.

Some scientists advise not making too much of

the finding, which was based on just one person

talking. Marr and her team were among the

scientists who responded with experiments of

their own, finding that neck gaiters blocked

most large droplets. Marr says she is writing up

her results for publication.

“There’s a lot of information out there, but

it’s confusing to put all the lines of evidence

together,” says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist

at Columbia University’s Mailman School of

Public Health in New York City. “When it comes

down to it, we still don’t know a lot.”

Questions about masks go beyond biology,

epidemiology and physics. Human behavior is core

to how well masks work in the real world. “I

don’t want someone who is infected in a crowded

area being confident while wearing one of these

cloth coverings,” says Michael Osterholm,

director of the Center for Infectious Disease

Research and Policy at the University of

Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Perhaps fortunately, some evidence

suggests that donning a face mask might drive

the wearer and those around them to adhere

better to other measures, such as social

distancing. The masks remind them of shared

responsibility, perhaps. But that requires that

people wear them.

Across the United States, mask use has held

steady around 50% since late July. This is a

substantial increase from the 20% usage seen in

March and April, according to data from the

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at

the University of Washington in Seattle (see go.nature.com/30n6kxv).

The institute’s models also predicted that, as

of 23 September, increasing US mask use to 95% —

a level observed in Singapore and some other

countries — could save nearly 100,000 lives in

the period up to 1 January 2021.

“There’s a lot more we would like to know,” says

Vos, who contributed to the analysis. “But given

that it is such a simple, low-cost intervention

with potentially such a large impact, who would

not want to use it”

Further confusing the public are controversial

studies and mixed messages. One study in April

found masks to be ineffective but was retracted

in July. Another, published in June, supported

the use of masks before dozens of scientists

wrote a letter attacking its methods (see go.nature.com/3jpvxpt).

The authors are pushing back against calls for a

retraction. Meanwhile, the World Health

Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially

refrained from recommending widespread mask

usage, in part because of some hesitancy about

depleting supplies for health-care workers. In

April, the CDC recommended that masks be worn

when physical distancing isn’t an option; the

WHO followed suit in June.

There’s been a lack of consistency among

political leaders, too. US President Donald

Trump voiced support for masks, but rarely wore

one. He even ridiculed political rival Joe Biden

for consistently using a mask — just days before

Trump himself tested positive for the

coronavirus, on 2 October. Other world leaders,

including the president and prime minister of

Slovakia, Zuzana Čaputová and Igor Matovič,

sported masks early in the pandemic, reportedly

to set an example for their country.

Denmark was one of the last nations to mandate

face masks — requiring their use on public

transport from 22 August. It has maintained

generally good control of the virus through

early stay-at-home orders, testing and contact

tracing. It is also at the forefront of COVID-19

face-mask research, in the form of two large,

randomly controlled trials. A research group in

Denmark enrolled some 6,000 participants, asking

half to use surgical face masks when going to a

workplace. Although the study is completed,

Thomas Benfield, a clinical researcher at the

University of Copenhagen and one of the

principal investigators on the trial, says that

his team is not ready to share any results.

For now, Osterholm, in Minnesota, wears a mask.

Yet he laments the “lack of scientific rigor”

that has so far been brought to the topic. “We

criticize people all the time in the science

world for making statements without any data,”

he says. “We’re doing a lot of the same thing

here.” The emphasis on gathering data rather

than understanding the processes and creating

accurate formulae seems to be a difference

between the medical community and those involved

with aerosol science. Droplet evaporation can be

predicted and there are experts to make the

calculations (see the MIilvaine interview with

the UCSD droplet expert).

This article by Lynne Peeples is found at

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02801-8

Glendale Arizona Buying Room Air Purifiers with

HEPA Filters

With in-person learning back among Deer Valley

Unified School District campuses, the district

this week will present on its emergency

acquisition of air purifiers and filters for

campus buildings in ongoing precautionary

efforts against coronavirus.

Director of Finance Heather Mock will submit the

request for a purchase total of $666,547.70 to

procure air purifiers and filters for all

district classrooms.

“Due to Covid-19 epidemic and updated

recommendation from the Maricopa County Public

Health Services – Ventilation in a School

Setting, Districts should use portable room air

purifiers with HEPA filters, especially in

higher-risk areas,” the district wrote of its

emergency incident. “Due to the current demand

for these air purifiers, these items are scarce

and have long-term delivery windows, which are

extending daily.”

“Therefore, due to time constraints and

availability, the district found it in the best

interest to prioritize and place the purchase

prior to the next scheduled governing board

meeting. The purchase was procured through an

approved Cooperative, due diligence was

performed, and quotes were obtained.”

The request states that Grainger provided the

best value and availability.

HEPA, or high efficiency particulate air

filters, “can theoretically remove at least

99.97 percent of dust, pollen, mold, bacteria,

and any airborne particles with a size of 0.3

microns,” according to epa.gov.

The first round of a staggered return to

live learning around the district came on Sept.

24. The final round will see K-8 middle school

grades and high school freshmen return to their

respective campuses on Wednesday, Oct. 14, at

which time all district campuses will be back to

full occupancy with safety guidelines in place.

NYC Indoor Restaurants Reopen with HEPA Filters,

UV and Ionizers

New York City reopened for indoor dining at 25

percent capacity starting on September 30.

There are requirements such as PPE for

the service people.

Top Line Hospitality Services owner Scott Bankey

has been upgrading restaurants’ HVAC units to

MERV-13.

On the roof of the Michelin-starred Musket Room

in Soho, Bankey installed a bit more:

ultraviolet lamps designed to inactivate up

to 99 percent of funguses, bacteria, and

viruses in

the air that’s been vented from the restaurant.

The sanitized air then hits the filter, is mixed

with fresh air, and is pumped back inside.

Musket Room staff were at first anxious about

serving unmasked customers indoors, but owner

Jennifer Vitagliano reviewed the additional

modifications with them so that they could

research it for themselves. “Everyone feels

really confident that we’re going above and

beyond to create a safe environment,” says

Vitagliano, who would not confirm the exact

price of the modifications but said that it cost

the restaurant “a few thousand dollars.”

William Bahnfleth, professor of engineering at

Penn State University, who focuses on HVAC

(heating, ventilation, and air conditioning),

thermal storage, and indoor air quality in his

research. He weighed in on UV.

“There’s a very

good track record for

UV, because it’s been used in infection control

since at least the 1930s,” says Bahnfleth, who

also serves as the chair of the epidemic task

force for ASHRAE (American Society of Heating,

Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers).

“It wasn’t something that most people were aware

of, but it’s been around for a long time. I’ve

been doing research on it for over 20 years.”

Le Bernardin, the only three-Michelin-starred

restaurant to reopen September 30 — the first

day indoor dining is allowed again in NYC has

installed a Needlepoint Bi-Polar Ionization

system, which they say is “proven to eradicate

99.4% of airborne COVID-19 particles within 30

minutes.” The technology sounds like the stuff

of science fiction: Charged particles are

released into the air to hunt for dust and

viruses, deactivating them upon contact. While

UV lamps rely on air that’s been sucked into the

HVAC unit to be sanitized, bi-polar ionization

systems are, in theory, proactive. Their

efficacy is still up for debate, since there

have been few peer-reviewed studies on the

technology.

“What ionizers definitely do is charge particles

so that they stick together and they can be

removed from the air more efficiently,” says

Bahnfleth. “Like UV, ionizers have been around

under the radar for quite a while, but they’re

just something everyone’s aware of now because

of the pandemic. They weren’t invented

yesterday.”

The cost of these units is high, especially for

restaurants that are already financially

strapped as a result of the pandemic. The team

at Crown Shy in the Financial District is

operating at just 10 percent of their

pre-pandemic revenue but spent $40,000 adding a

bi-polar ionization system to the HVAC units

that service both the ground-floor restaurant

and its soon-to-open restaurant

in the sky,

Saga.

“It’s expensive, but it’s worthwhile,” says

general manager and partner Jeff Katz. “Our

first concern is making people feel comfortable

in the space, so that they can think as little

as possible about the global pandemic. Nothing

ruins a meal like the thought of pathogens.”

AtmosAir, which manufactures the units that were

installed in Crown Shy, has seen its revenues

rocket to five to six times what it was at this

point last year. “Demand is very high in New

York City,” says Brian Levine, AtmosAir’s vice

president of marketing.

Coronavirus preparation, like most other things,

is a battle between the haves and have nots.

Smaller neighborhood joints are more likely to

just buy HEPA air filter units for several

hundred dollars. But an organization like Union

Square Hospitality Group, which operates

restaurants like Gramercy Tavern, Blue Smoke,

and Union Square Cafe, can afford to leave no

box unchecked, spending tens of thousands of

dollars to beef up its filtration systems,

adding both a UV light rig and bi-polar ionizer

at each of its locations.

While these extra precautions may be helpful to

ease the minds of a shell-shocked population,

the state reopening guidelines also recommends

simple things like a basic ventilation system or

even leaving all the doors and windows open.

Restaurants in the Northeast and the rest of New

York State have been open for indoor dining for

months without a surge in coronavirus cases,

despite many places lacking the resources to

install high-end HVAC systems.

In recent interviews,

the nation’s leading infectious disease expert,

Dr. Anthony Fauci, stated that dining indoors

“absolutely increases the risk,” but stressed

the importance of harm reduction in dealing with

COVID-19. “There comes a point where you’ve got

to accept human nature,” Fauci said of people’s

desire to socialize. He added that in addition

to a low local positivity rate, “anything that

has airflow out, not airflow in the room” was

the key to making restaurants safer.

“There’s a lot of evidence that good ventilation

is protective,” says Bahnfleth. “And when you

add filters to it and air cleaners, things get

even better.”

https://ny.eater.com/2020/9/30/21494934/nyc-restaurants-indoor-dining-air-filters-cost-coronavirus

Meat Packers Need Efficient Masks and Fan Filter

Units

There is an extensive analysis of the meat

packing industry attempts to protect workers in

Mother Jones by Tom Philpott.

He is the food and ag correspondent for Mother

Jones. He can be reached at

tphilpott@motherjones.com, or on Twitter at

@tomphilpott.

We are showing the Philpott analysis with our

comments in italics. The coronavirus has fallen

heavily on the people who cut and pack the US

meat supply. After blitzing meatpacking plants

all spring and summer, the illness has infected

at least 43,100 of these workers and killed 206,

according to the running tally kept by the Food

and Environment Reporting Network’s Leah

Douglas. Lately, new cases and deaths within the

industry have been leveling off, according to

Douglas’ data. And media attention has shifted

from the deadly toll on workers to the gentle

penalties the Trump administration has imposed

on the massive companies that dominate the meat

industry for their worker-safety performance

during the crisis.

Though it’s failed to garner much national

attention, the deadliest meatpacking outbreak of

all has unfolded in recent weeks in California’s

agriculture-dominated San Joaquin Valley. On

September 1, West Coast poultry powerhouse

Foster Farms closed its Livingston, California,

chicken plant by order of the Merced County

Department of Public Health,

after acknowledging 392 positive COVID-19 tests

and eight deaths among employees. After another

plant employee who had been hospitalized with

COVID since August died in mid-September, the

outbreak’s death toll now stands at nine, the

most COVID-related fatalities of any single

meatpacking plant, according to FERN’s Douglas.

Could the company have done more to prevent the

outbreak? The Merced County health department

repeatedly warned Foster Farms to ramp up

efforts to protect its employees, before any

deaths occurred. In an August 27 press

release, the health department reported that it

had been unsuccessfully urging Foster Farms to

take precautionary safety measures since late

June, a “month prior” to any COVID-related

deaths.

On June 29, as COVID cases at the plant

“continued to rise,” county health officials

inspected the plant. To limit the outbreak, the

health department suggested “significant changes

to the employee break spaces and performing

widespread testing of employees within the

facility.” The department continued to call for

a testing ramp-up throughout the month of July,

but by the final days of the month, Foster Farms

had “tested less than 10 percent of the

department with the largest [COVID] impact

within the facility,” the report states. Among

the employees who were tested, more than 25

percent turned up positive.

In August, the department stepped up its

campaign to push Foster Farms to increase

testing and tweak common areas. On August 3,

officials made a second visit to the Foster

plant—this time accompanied by representatives

of Cal/OSHA, the state’s worker-safety

enforcement agency. On August 5 and 11, the

department repeated its call on the company to

increase employee testing and tweak common areas

to enable social distancing. Meanwhile, the

coronavirus continued to spread through the

complex, “posing a significant threat to Foster

Farms employees and the surrounding community,”

the health department report states. Finally, on

August 27, two months after its initial call for

common-area changes and widespread testing, the

health department ordered the plant to

close, pending universal employee testing and

“significant changes” to all break spaces and

“areas of potential congregation” to “ensure

adequate social distancing of all workers on the

plant.” In the period of time between the

initial June 29 recommendations and the August

27 close order, eight workers died of COVID-19.

The company failed to keep workers informed

about the outbreak as it spread through the

plant over the summer, says Erika Navarrete of

the United Farm Workers of America, which

represents the plant’s workers. Workers have

told Navarrete that Foster Farms has only given

them two masks per person total since the start

of the pandemic, so they’ve had to buy this

crucial protection themselves. And while the

company has installed plexiglass barriers

between stations on the facility floor, “workers

are still too close together,” working

shoulder-shoulder on the line, says Navarrete,

who has visited the plant several times. A

Foster Farms spokesperson declined to comment.

The conditions described by Navarrete—masked

workers toiling close together, separated by

plastic barriers—appear to be standard

poultry-industry practice during the COVID

crisis. In an article entitled

“Our #1 Priority: Keeping Chicken Company

Employees Safe & Healthy During COVID-19,” the

National Chicken Council—a trade group

representing US chicken processors—includes the

below photograph of workers on a

chicken-production during the pandemic. A

National Chicken Council spokesperson alerted

that meat giant Tyson Foods had posted the photo

on a web gallery available to media showing the

“protective measures” the company is taking in

response to COVID-19.

Is the arrangement sufficient to protect workers

from COVID? Federal worker-safety authorities

are fuzzy on the topic. The US Occupational

Safety and Health Administration has declined to

issue binding workplace regulations to impede

the spread of COVID. Along with the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, OSHA released voluntary

meatpacking-industry guidelines on

July 26. The guidelines call on companies to

“modify the alignment of workstations, including

along processing lines, if feasible, so that

workers are at least six feet apart in all

directions (e.g., side-to-side and when facing

one another), when possible.” They also suggest

“physical barriers, such as strip curtains,

plexiglass or similar materials…to separate meat

and poultry processing workers from each other.”

The guidelines don’t comment on whether barriers

negate the need for social distancing.

Two independent occupational health experts

Philpott consulted

say distancing is essential, with or without

barriers in place. “Medical masks and plastic

sheeting are not enough,” said David Michaels,

who served as chief of the Occupational Safety

and Health Administration under President Barack

Obama and is now a professor of environmental

and occupational health at George Washington

University. He pointed to a July 2020

investigation by

German scientists of a COVID-19 outbreak in a

German meatpacking plant which found that

“climate conditions and airflow” in these plants

can “can promote efficient spread” of the virus

at “distances of more than 8 meters,” or 26

feet. “Workers in poultry plants need greater

distance between them, and they need

respirators, not medical masks,” Michaels said.

The important point here is that you need

respirators not masks. Furthermore these

respirators have to be tight fitting. Look at

this picture and

envision that many of the workers are

smoking cigarettes. How effective would the

partitions or loose fitting masks be?

Plastic barriers are “more effective in a

grocery store situation where you’re having very

quick interactions with people,” said Marissa

Baker, director of the Industrial Hygiene

Training program at the University of

Washington’s Department of Environmental &

Occupational Health Sciences. But in meatpacking

plants, “you’re standing shoulder to shoulder

with someone for eight hours a day—unless you’re

in your own separate box, there’s definitely a

chance for virus to get around those barriers.”

She said a safer approach would be to keep the

barriers but spread workers at least six feet

apart—which would likely require the company to

slow down its production. A slower line would

also protect workers from COVID-19 in another

way, Baker added: “When you have people working

fast, people are breathing harder—and that leads

to more particle generation,” and thus more

potential exposure to pathogens.

You could keep the close spacing if you have fan

filter units spaced along the line. The downward

clean air flow will keep the virus from moving

horizontally.

“Medical masks and plastic sheeting are not

enough,” according to occupational safety expert

David Michaels.

When the COVID crisis took root in the spring,

Foster Farms joined several other meatpacking

companies in delivering its workers a salary

bonus of $1 per hour for working

shoulder-to-shoulder during a pandemic. But the

company ended the bonus on May 31—just before

the disease began to spread through the plant,

Navarrete said. UFW is currently negotiating

with Foster Farms on a contract for the plant’s

workers, she added, and is demanding $2 per hour

hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic.

It remains to be seen whether Foster Farms will

face penalties for its management of the

Livingston outbreak. So far, despite widespread

contagion and fatalities in plants across the

country, Trump’s OSHA has doled out two fines—at

levels that Michaels, the former OSHA

administrator, has called “less

than a slap on the wrist.” Trump’s OSHA

recently hit pork

giant Smithfield with a $13,494 fine for an

April outbreak that infected at least 1,294

workers and killed 4 at its massive pork

operation in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; and it

laid a $15,615 penalty on meatpacking behemoth

JBS for

an outbreak that led

to 300

positive tests and six worker deaths at its

Greeley, Colorado, beef plant.

In California, worker-safety laws are enforced

by a state agency called Cal/OSHA, a division of

the California Department of Industrial

Relations. On September 9, Cal/OSHA hit mid-sized

frozen-foods manufacturer, Overhill Farms, with

a $200,000 fine, and levied another $200,000 one

on the temporary-employment agency it uses,

Jobsource North America. Their infraction,

according to the press

release:

They failed to take measures to protect workers

from COVID-19, resulting in “more than 20

illnesses and, in the case of Overhill Farms,

one death.”

On September 8, Foster Farms reopened its

Livingston plant after complying with health

department conditions. Whether

it will pay a price for the outbreak remains to

be seen. In an email, a spokesman for the

California Department of Industrial Relations

wrote: “Cal/OSHA opened an inspection on July 23

at the Foster Farms in Livingston after

notification that a worker died from

complications related to a COVID-19 infection.”

He declined to comment further on what he called

an “ongoing inspection” of the plant, but added

that “by law, Cal/OSHA has up to six months from

the opening date of an inspection to issue

citations.” In the meantime, dozens of workers

in the plant continue to work shoulder to

shoulder as the pandemic grinds on.