Coronavirus Technology Solutions

September 30, 2020

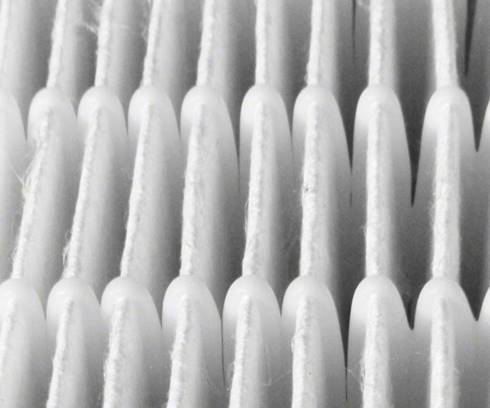

IQ Air NanoMx and HyperHEPA Pleat Filters

Media Starting to Understand that only Efficient

Masks are Effective

Heating and Humidity to Decontaminate Masks

New York

Closes School Due to Two Cases of the

Virus

Italy Reduces Case Load with Testing of

Youngsters

Evidence Continues to Show that We Need

Efficient Masks

______________________________________________________________________________

IQ Air NanoMx and HyperHEPA Pleat Filters

NanoMax filters reduce fine and ultrafine

particles by up to 95%, including viruses,

bacteria, allergens, and harmful traffic

pollutants. NanoMax filters eliminate the need

for costly upgrades to a building’s HVAC system

typically associated with HEPA filters. NanoMax

filters require no prefilters, fit into standard

2” filter slots, and have pressure drops fully

compatible with standard HVAC systems.

NanoMax filters exceed MERV 16 requirements per

ASHRAE 52.2 standards, designed to capture up to

95% of even the smallest and deadliest airborne

particles: PM2.5 (< 2.5 microns) and ultrafine

particles (< 0.1 microns), which can get into

your bloodstream and cause systemic health

effects, including dust, mold, viruses,

bacteria, allergens, and harmful traffic

pollutants.

Advanced HyperHEPA pleat design allowed IQAir

designers to build in 60 square feet of surface

area – five times more than the surface area of

a conventional pleated air filter. The result is

increased airflow and better filter loading,

which widens replacement intervals and reduces

costs.

Media Starting to Understand that only Efficient

Masks are Effective

Here are excerpts from a recent article showing

that only efficient masks are effective against

COVID.

New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and other states

are requiring everyone to wear a mask or a

substitute face covering to leave home. The

federal Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention has suddenly flipped from urging the

public not to wear masks to recommending that

they wear something that covers their nose and

mouth.

New York's Mayor Bill de Blasio's new signature

look is a western-style bandana pulled up over

his mouth and nose. No doubt he's

well-intentioned. But that kind of face-covering

is only a hair better than no covering at all.

Science shows it's a mere 2% to 3% effective.

It's misleading.

From Day One of the coronavirus outbreak, the

public has gotten the run around about masks.

Government officials need to be honest about

what works and what doesn't. Here's the

scientific evidence:

N95 masks, which are molded and fit tight to the

face, filter out 95% of viral particles, even

the smallest ones. These masks offer the best

protection, but they are in short supply, and

public officials want them reserved for health

care workers on the front lines.

Surgical masks, the kind you see commonly worn

in hospitals and dentists' offices, are flat and

held to the face with elastic. They're made from

a nonwoven material, polypropylene, that is a

somewhat effective filter. They protect the

wearer from about 56% of viral droplets emitted

by an infected person nearby, according to

research in the British Medical Journal.

Not so woven cloth masks. They allow in 97% of

viral particles. That means almost no protection

for the wearer.

Wearing a homemade cotton mask is a false

assurance, explains epidemiologist May Chu. She

says it will block only about 2% of airflow.

Similarly, a study in Disaster Medical and

Public Health Preparedness concludes that a

homemade mask should be considered "only as a

last resort," better than no protection at all

but not a lot better.

Surgical masks seem available in stores now, and

if you can buy a supply, using them is far

preferable to make your own. Don't reuse the

mask and avoid touching the outside of the mask,

because it's likely contaminated after use.

If you have to resort to homemade barriers, keep

in mind that the more layers of cloth, the

better the protection. Four layers likely block

out 13% of viral droplets, compared with the 2%

blocked with a single layer, according to a

study in Aerosol and Air Quality Research.

Why are public officials suddenly urging mask

use, many weeks after the coronavirus struck?

Because of mounting research pointing to the

huge role of asymptomatic people spreading the

disease before they feel ill. Whenever these

asymptomatic carriers talk or simply exhale,

they spread very small droplets of virus-laden

saliva and respiratory mucous in the air.

Scientists call it bioaerosols.

Getting everyone to mask up does double duty --

helping to protect the uninfected and keeping

the unknowingly infected from spreading the

virus. As New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said,

announcing the mask mandate: "You don't have a

right to infect me."

That makes sense, but Americans have had to put

up with a lot of message confusion from the

outset, and now they're getting misleading

advice about homemade masks.

What's the root problem? Year after year after

year, through three presidencies, federal health

bureaucrats ignored warnings about inadequate

supplies of masks and other equipment in the

event of a pandemic. Ten federal reports sounded

the alarm, even as the nation witnessed SARS,

MERS, avian flu and swine flu that circled the

globe. In 2009, during the swine flu outbreak,

the federal Strategic National Stockpile

dispersed 85 million N95 masks, as well as other

protective masks. The masks were never replaced.

Don't blame any president, Democratic or

Republican, for this oversight. The career

officials at Health and Human Services knowingly

allowed the nation to be undersupplied. They

never requested enough money to adequately stock

the Strategic National Stockpile. Their agenda

was global, tracking down polio in Pakistan,

pouring nearly $5 billion in the fight against

Ebola overseas and funding a Global Health

Security Agenda serving 49 countries. But no

masks for Americans.

When the coronavirus struck, the CDC offered

only mask double talk. The agency said, on the

one hand, masks are vital to protect health care

workers, and on the other hand, masks won't make

the public safer. It defies common sense. The

agency should have leveled with people,

admitting supplies had to be saved for front

line caregivers.

The coronavirus could return next winter. Or

another viral pandemic could strike from any

part of the globe. The bill Congress enacted in

late March allocates $16 billion to the

Strategic National Stockpile, nearly 30 times

its annual budget. Next time, the U.S. will have

enough masks.

Heating and Humidity to Decontaminate Masks

Scientists out of Department of Energy’s SLAC

National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford

University and the University of Texas Medical

Branch have now found a technique, which could

allow the masks to get disinfected and make it

safer for reuse.

According to researchers, something simple as

'heating' the mask could relatively disinfect

the virus and help recycle them for further use.

The strategy, which researchers feel which

definitely help healthcare workers at a time

like this could lessen the shortage problem and

not contribute to the pandemic pollution as

well.

“You

can imagine each doctor or nurse having their

own personal collection of up to a dozen masks.

The ability to decontaminate these for reuse

would ease the shortage.

While there are no studies yet to confirm the

reaction of the novel coronavirus in contact

with high temperatures, scientists based out of

Stanford University devised a novel way of

combining heat and humidity to decontaminate and

inactivate the viruses at large.

Conducting the experiment in a safe environment,

scientists mimicked real-life situations by

mixing up SARS-COV-2 strains in liquids like the

fluids which come out of our mouth while a

person coughs, sneezes or breathes.

The droplet solution was then made to air dry on

a special meltblown polypropylene fibres fabric,

which is also used in the making of N95 masks

and then heated at different temperature

settings, for 30 minutes.

It was observed that the environment with high

humidity and heat was able to reduce the virus

load on the fabric. However, extreme heat

reduced the mask's sensitivity to filter out

germs and viruses.

The best temperature, for 'cooking' and rooting

out the viruses turned out to be 85-degree

Celsius, with 100% relative humidity. Scientists

were able to observe zero trace of the COVID

causing virus after sample masks were treated

under the given environment.

Additionally, it was also observed that the

method would decontaminate the mask and make it

suitable for use up to 20 times, which could

potentially help save resources.

Further, the virus killing technology could also

be useful to on other types of PPE.

New York Closes School Due to Two Cases of the

Virus

A city school has been closed for two weeks due

to the coronavirus – the first extended

shuttering this year, officials revealed

Thursday.

The John F. Kennedy Jr. school in Elmhurst is

the first city school to trigger a 14-day

quarantine protocol after it confirmed two

unrelated coronavirus cases among staffers.

Prior to the start of the academic year, the

Department of Education said it would take the

action when two or more COVID-19 infections

arise at the same school with no links between

infected students or staffers.

Administrators at the special needs high school

sent out a letter alerting parents and students

of the closure this week.

“We hope to return to the building on Wednesday,

October 13,” the message read.

Administrators said anyone who eventually tests

positive won’t return until they are no longer

infectious and that close contacts will be

instructed to quarantine.

The closure will impact 262 kids at the school

who are enrolled in a blended learning model.

All students will now learn remotely until the

doors reopen.

Mayor Bill de Blasio stressed Thursday that the

John F. Kennedy Jr. is the only one of the

city’s 1,600 schools to require a two-week

closure thus far.

The two cases were identified by City Hall’s new

“Situation Room” that monitors school

infections.

“That’s the only one the entire time that has

experienced that,” de Blasio said during his

daily press briefing. “And what’s going to

happen, I think, in a case like this is what

we’ve been telling people along those two weeks,

kids, of course, will get instruction remotely,

then the school will be a backup to everyone who

was quarantine will come right back,”

According to the DOE, 160 schools have reported

isolated coronavirus cases. In those scenarios,

schools are only required to close for 24 hours

before being allowed to reopen.

“We won’t hesitate to take quick action for the

health and safety of our school communities, and

that’s exactly what we did when two positive

cases amongst staff members were identified at

John F. Kennedy High School,” said DOE spokesman

Nathaniel Styer.

The department said that an investigation at the

school confirmed two cases among staff members

within a 7 day period.

Italy Reduces Case Load with Testing of

Youngsters

Through the window of the car in front, there's

a short, sharp cry from the toddler - eased with

a quick lollipop or a colorful picture: a

distraction aid once the swab is finished. And

then the next in a long line of vehicles pulls

up as Rome's "Baby drive-in" continues apace.

The test serves children from

newborn to the age of six. A result comes within

30 minutes. If it's negative, they can return to

day-care or school, even if there's a positive

case in their class.

It's the latest innovative initiative by the

country that was the first in Europe to be

overwhelmed by coronavirus but which is for now

managing to keep the virus in check more

successfully than many others.

Italy's cumulative number of Covid cases over

the past two weeks is currently just over 37 per

100,000 people, among the lowest rates in

Europe. The UK is at over 100, France exceeds

230 and Spain has around 330.

"February and March were very hard," says

Elisabetta Cortis, one of the pediatricians who

founded the drive-through project. "And then we

suffered a lot because with the lockdown, we had

many problems for the kids. They stayed alone -

no friends, no school, no sport, nothing."

It is actually difficult to pinpoint exactly why

Italy is somewhat bucking the trend of European

countries experiencing an alarming spike in

cases.

Its testing rate is not exceptionally high - the

UK is carrying out over three times the tests of

Italy - but the swabs are widely available and

rapid testing is now in place at some airports,

train stations and schools, so there is no sign

of the problems in accessing tests that have

been seen in the UK and elsewhere.

The most likely explanation is a combination of

factors: efficient test and tracing, a longer

lockdown - Italy was the world's first country

to shut down nationwide and among the slowest to

reopen - and the fact that the trauma of the

early weeks of the pandemic frightened Italians

into widespread compliance with rules.

At Tonarello, a pasta restaurant in the Roman

district of Trastevere, several measures are in

place, including plexiglass screens between

tables, the recording of customers' details for

contact tracing and disposable paper menus. Some

other restaurants and cafes use digital QR codes

for menu access on smart phones.

Italy was one of the slowest

countries to reopen schools - and that only now

is the hot summer beginning to break, the cold

weather bringing with it the increased risk of

contagion.

So it is possible that Italy,

ahead of the rest of Europe when Covid arrived,

is behind the curve as its neighbors struggle

with a spike.

But for now the figures look

promising. And that simple formula - tests,

rules, compliance - will, this country hopes,

halt a second wave and ease the legacy of pain

from the first.

Evidence Continues to Show that We Need

Efficient Masks

There is a battle over the importance of mask

efficiency which was reported this week in

Scientific American. In one corner, we have

scientists, epidemiologists, infectious-disease

physicians, clinicians, engineers—many different

experts in the medical community, that

is—arguing that the spread of COVID-19

by aerosols (that is, tiny droplets that can

remain airborne long enough to travel

significantly farther than the six-foot

separation we’ve been told to observe) is both

real and dangerous. In the other, it’s

the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and

the World Health Organization (WHO), which until

very recently

have allowed only that aerosol spread is possible,

not necessarily likely.

Droplets are relatively large. Aerosols, on the

other hand, are tiny by comparison,

nearly 10,000 times smaller than a human hair.

They’re spread at far greater distances—20 to 30

feet—and can linger in the air for minutes

to hours, infecting others. What constitutes a

safe distance from aerosols is much harder to

define, especially in crowded indoor spaces with

poor ventilation. Choosing a safe mask becomes

difficult as well: an N95 respirator, for

example, would be preferable to an ill-fitting

cloth mask when it comes to filtering out these

minuscule viral aerosols. For these and other

reasons, some in the medical community suspect,

our health agencies have been reluctant to

accept the data on the airborne transmission of

COVID-19—because if they do, they’re

acknowledging a problem far more challenging

even than what we’ve been dealt with so far.

This reluctance has prompted an epic response.

In a nearly unprecedented move, 239 scientists

from 32 countries wrote an open letter to the

WHO in July, urging the agency to recognize that

airborne transmission of coronavirus by smaller

aerosol particles is possible. The

organization’s response was to subsequently

update its position, stating that aerosol

transmission “cannot be ruled out.” A glowing

endorsement this was not. The CDC,

meanwhile, posted on its Web site over the

weekend that aerosolization may be “the main way

the virus spreads,” then backtracked and removed

the content from its site, claiming the language

had been a draft of some proposed changes which

were “posted in error.”

This is a major point, not a minor one. Aerosol

carry of the virus means that any indoor area

where people gather in numbers—think

restaurants, bars, churches, schools, rallies—is

potentially a spreader of the disease, and

depending upon the numbers, a superspreader.

These are likely places with poor ventilation,

where people not only are close together but may

be speaking loudly, shouting, singing, cheering

or booing, etc.

The idea of aerosol spread is neither new nor

controversial. Several diseases,

including measles, chickenpox and

tuberculosis, have been shown to be transmitted

by aerosols. Patients sick with the flu have the

virus in their exhaled breath, and

that virus has been shown to be present in

the air. This is true for some other viruses,

including those found in infants.

Scientists in Wuhan, China, have identified

coronavirus RNA particles in the air in hospital

areas, although they haven’t yet proven that the

particles are infectious. Lab workers at the

University of Nebraska have published their

finding that they, too, have identified

coronavirus RNA in the air.

“We have pretty strong circumstantial

evidence, in a number of these superspreading indoor

incidents, that there must have been a

significant component of aerosol or airborne

transmission,” says William Bahnfleth, chair of

the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating

and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Epidemic

Task Force. Bahnfleth noted several examples,

including a restaurant in Guangzhou, China,

where multiple people without direct contact

with one another became infected from a single

individual, and a choir practice in Washington

state where presumed droplet and aerosol spread

from singing sickened

53 people, two of whom died.

In an e-mail interview, researcher Bjorn Birnir

shared his work, published in a preprint (a

non–peer reviewed paper), that demonstrated how

an infected person continues to exhale a cloud

of droplets and aerosols. These “build up over

time to dangerous concentrations for everyone in

the room,” Birnir says. While we don’t know

exactly how much virus is needed to infect

people or at what concentrations, these examples

show that at some point the threshold is met and

inhaled aerosols are the likely culprits.

“Aerosol transmission plays a significant role

in indoor environments and cannot be neglected,”

says environmental science expert Maosheng Yao,

a professor of engineering at Peking University.

“Sooner or later, [the WHO] is going to

recognize this officially.”

Much of the solution to the challenge of aerosol

(and droplet) transmission in indoor areas is

ventilation. “If people use recirculated air

during a pandemic, it is going to be dangerous,

because you will just circulate the virus

around,” Yao says. The goal of ventilation,

instead, is to exhaust air from inside a

building—along with whatever contaminants it

contains—and replace it with clean air from the

outside.

High efficiency air filtration and disinfection

are important. Filters should be upgraded to the

extent possible in HVAC systems without

diminishing airflow. The ASHRAE paper recommends

MERV-13 filters or the highest level allowable,

which filter very small infectious particles.

And if HVAC units cannot use higher-grade

filters, consider using portable air cleaners

with HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air)

filters to disinfect the air further.

A word about ultraviolet light. “A coronavirus

is a coronavirus,” says Bahnfleth, and

prior studies found that ultraviolet light

inactivated other coronaviruses, like SARS-CoV-1

and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome). UV

fixtures can be mounted on the ceiling or walls

or placed inside ventilation ducts to neutralize

viruses and bacteria. The biggest limitation is

that the irradiation can be a health hazard, to

both skin and eye, which is why the fixtures are

placed up high, away from people.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/protecting-against-covids-aerosol-threat/