Coronavirus Technology Solutions

June 16, 2020

Elastomeric Masks

are the Choice for AHN

UV Sterilization does not Impact Mask Efficiency

According to ASU Studies

Ultraviolet

Sanitization Kit for Masks, Wallets, Keys and

Glasses

North Carolina Meat and Poultry Industry has

Major COVID Problem

Social Distancing is not a Safe Solution

____________________________________________________________________________

Elastomeric Masks

are the Choice for AHN

A cost-effective strategy for health care

systems to offset N95 mask shortages due to the

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is

to switch to reusable elastomeric respirator

masks, according to new study results. These

long-lasting masks, often used in industry and

construction, cost at least 10 times less per

month than disinfecting and reusing N95 masks

meant to be for single use, say authors of the

study, published as an "article in press" on

the Journal of the American College of

Surgeons website in advance of print.

The study is one of the first to evaluate the

cost-effectiveness of using elastomeric masks in

a health care setting during the COVID-19

pandemic, said Sricharan Chalikonda, MD, MHA,

FACS, lead study author and chief medical

operations officer for Pittsburgh-based

Allegheny Health Network (AHN), where the study

took place.

Disposable N95 masks are the standard face

covering when health care providers require

high-level respiratory protection, but during

the pandemic, providers experienced widespread

supply chain shortages and price increases, Dr.

Chalikonda said. He said hospitals need a

long-term solution.

"We don't know if there will be a shortage of

N95s again. We don't know how long the pandemic

will last and how often there will be virus

surges," he said. "We believe now is the time to

invest in an elastomeric mask program."

Dr. Chalikonda said an immediate supply of

elastomeric masks in a health care system's

stockpile of personal protective equipment is

"game changing" given the advantages.

Elastomeric masks are made of a tight-fitting,

flexible, rubber-like material that can adjust

to nearly all individuals' faces and can

withstand multiple cleanings, Dr. Chalikonda

said. These devices, which resemble gas masks,

use a replaceable filter. According to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC), elastomeric masks offer health care

workers equal or better protection from airborne

infectious substances compared with N95 masks.

Like many hospitals during the COVID-19 crisis,

AHN was disinfecting and reusing N95 masks for a

limited number of uses. However, Dr. Chalikonda

said, "Many caregivers felt the N95 masks didn't

fit quite as well after disinfection."

At the end of March, AHN began a one-month trial

of a half-facepiece elastomeric mask covering

the nose and mouth. The mask holds a P100-rated

cartridge filter, meaning it filters out almost

100 percent of airborne particles.

Until AHN could procure more elastomeric masks,

the system began its program for P100

elastomeric mask "super-users": those providers

who have the most frequent contact with COVID-19

patients. At each of AHN's nine hospitals in

Pennsylvania and Western New York, the first

providers to receive the new masks were

respiratory therapists, anesthesia providers,

and emergency department and intensive care unit

(ICU) doctors and nurses. Initially, providers

shared the reusable masks with workers on other

shifts, and the masks underwent decontamination

between shifts using vaporized hydrogen peroxide

similar to the technique used to sterilize

disposable N95 masks.

Another advantage of an elastomeric respirator

program, according to Dr. Chalikonda, is it does

not require any additional hospital resources to

implement if the hospital already has an N95

mask reuse and resteriliation program. The AHN

elastomeric mask program presented fewer

operational challenges than disinfecting N95

masks, he stated.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/06/200612172222.htm

UV Sterilization does not Impact Mask Efficiency

According to ASU Studies

Sterilization may alter mask structure and

therefore the effectiveness of the mask’s

ability to block small droplets and aerosols.

Airborne particles and droplets, from a few

nanometers to a few microns in size, are the

research focus of School of Molecular Sciences

Professor Pierre

Herckes.

Herckes and his graduate student researcher,

Zhaobo Zhang, were testing personal protective

equipment (PPE) mask efficiency to trap

nanoparticles in the semiconductor industry

prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. After the

outbreak, they were approached by several groups

to test mask efficiency before and after

sterilization. Sterilization methods included

treatment with ultraviolet (UV) light, ozone, or

peroxide vapors. Before and after each of these

sterilization methods, Herckes and Zhang tested

the efficiency of masks to trap droplets and

aerosols.

“What we found was there was not a significant

decrease in mask efficiency before and after

treatment," Herckes said. "However, further

testing needs to be done to determine the effect

of multiple treatments on the structure of mask

materials.”

Herckes notes that their testing methods differ

from National Institute for Occupational Safety

and Health methods, but nevertheless provide

important results.

Herckes is co-investigator with ASU engineering

professor Paul Westerhoff on a recently funded

National Science Foundation grant, “Disinfection

and Reuse of Health-Care Worker Facial Masks to

Prevent Infection coronavirus disease.” This

grant allows Westerhoff and Herckes to test for

change in mask efficiency after repeated

UV-light exposure.

“This research is important because we know very

little about how UV-light modifies the molecular

structure of protective masks,” Herckes said.

Their work will also allow them to determine

mask efficiency based on particle size and

charge.

Large droplets, such as those produced when

someone coughs or sneezes, are trapped to a

great degree by a mask, and these droplets don’t

travel as far as smaller droplets. Smaller

droplets, however, are also capable of carrying

coronavirus particles. Coronavirus particles are

also transmitted by smaller particles, such as

those produced by talking or breathing. These

small droplets stay in the air much longer than

large droplets, and they are inhaled more deeply

into your lungs.

“Wear a mask, because it not only protects you,

but it protects others,” Herckes said.

Protection from a mask is greatest when it is

worn properly.

“Wearing a mask below your nose allows you to

inhale and exhale droplets, so cover your nose

with the mask, and make sure it fits properly

around your face so there isn’t leakage from the

sides,” he said. If air goes around the mask,

it’s not effectively trapping particles.

Herckes also advises that you minimize touching

your mask once it’s on.

“Your mask should be comfortable and not

restrict air flow significantly," he said. "When

you touch your mask, you are transmitting

contaminants from your hands to your mask, and

from your mask to your hands. More importantly,

the mask will trap airborne virus particles, so

you will be transferring these trapped particles

to your hands, and then from your hands to

whatever you touch, possibly your face, eyes and

mouth.”

Ultraviolet

Sanitization Kit for Masks, Wallets, Keys and

Glasses

Thanks in large part to COVID-19, though clearly

needed long before any international outbreaks,

ultra-violet sanitization kits are finally

coming to market, offering portable pouches that

kill 99.9% of common bacteria, coronaviruses

and, potentially, novel coronavirus,

all within minutes. Phuong Mai, founder and CEO

of P.MAI.,

recently released the travel-friendly Violet

Clean Kit, which

may be the very best way to sanitize your face

mask, phone, keys and more.

The partially collapsible, plug-in bag uses UV-C

light in a fully-reflective interior to sanitize

any small device, gadget or accessory in three

minutes, and is equally as convenient on the go

as it is for daily use in your own home.

Many of the other sanitizers have fewer and less

powerful UV lamps than Violet uses . It uses 12

powerful UV-C lights powered at nearly 10

milliwatts. Their Clean Kit has been

specifically engineered for optimal UV-C light

at germicidal wavelengths. The reflective

interior and magnetic zippers ensure the light

stays in and does not leak, and the convenient

size makes it easily portable. The bag's modern

design is also waterproof and oil-proof. Plus,

you can use the charging cable and dual power

adapter to charge your phone at the same time.

While some products use a 1 amp or 1.5 amp power

adapter, Violet

specifically use a 2A/5V to ensure optimal

output and efficiency.

It is recommended to sanitize phones, keys,

wallet, face mask and sunglasses after being

outside or around people.

North Carolina Meat and Poultry Industry has

Major COVID Problem

The meat and poultry industry in North Carolina

hires over 35,000 workers in the state and can

employ more than 4,000 workers in a single

facility. The state is continuously ranked among

the top five U.S. producers of chickens and

hogs.

But another statistic has emerged in the

industry with grim consequences: Plants that

process meat and poultry also are a breeding

ground for coronavirus. In North Carolina

processing plants, more COVID-19 outbreaks have

occurred than any other state, according to

the Food & Environment Reporting Network (FERN).

When outbreaks occur at densely populated

workplaces like meatpacking plants, it’s not

just the workers who are affected — they can

carry the virus back to their families and

communities. State health data on COVID-19

cases per ZIP code analyzed

by The News & Observer offers a look into the

potential scale of the outbreaks around several

key processing plants.

Coronavirus cases and infection rates per 10,000

residents have risen higher in the zip codes of

counties with significant plant outbreaks — like

Mountaire Farms in Chatham County — compared to

ZIP codes in counties without processing plants.

Across 13 ZIP codes near processing plants with

outbreaks in seven North Carolina counties,

virus cases rose by nearly 600% on average from

May 1 when the data was first released up to

June 11.

In contrast, the number of cases statewide in

the same time frame rose by 262%.

Over 2,000 processing plant workers so far have

tested positive for the coronavirus, according

to state health officials. Not all infected

workers live in the same counties or ZIP codes

they work in, highlighting the potential of

virus spread.

The infection rate per 10,000 residents in these

counties is higher than those of more populous

counties with higher overall cases like Wake,

Durham and Mecklenburg, according to the state’s

daily ZIP code virus data. Here is a

county-by-county look at some of the most

affected areas:

Chatham County

The Mountaire Farms poultry farm in Siler City,

one of the major employers in Chatham County

employing around 1,600 workers, has had

outbreaks since early April. Its ZIP code of

27344 has one of the highest case numbers in

North Carolina with 510 cases as of June 8.

An outbreak is defined by the Centers for

Disease Control as more than two coronavirus

cases.

COVID-19 testing of plant workers and their

families resulted in 74 positive cases among 340

people in late April, The

N&O reported previously,

but the plant

hasn’t reported an updated number of cases

since.

Mountaire is a main employer of many Latinos of

Siler City, who make up 43% of its population,

according to recent census data. Most are

immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

According to Chatham’s newly released ethnicity

COVID-19 data, Latinos are 34% of its positive

cases. But Latinos make up only about 10 percent

of the county’s population.

Robeson County

Three pork and poultry plants with outbreaks —

Mountaire Farms, Sanderson Farms and Prestige

Farms — are located in Robeson County. The

county’s health department told The N&O that by

the end of May, Mountaire had 61 cases, Prestige

had nine and Sanderson had five.

The world’s largest pork processing plant is

Smithfield Foods, which is in adjacent Bladen

County. That plant had 92 cases of workers who

are Robeson residents, the county health

department said.

Several other county health departments told The

N&O previously that some of their residents were

infected through working in that Bladen County

plant. As of June, at least nine residents of

Columbus County, three in Scotland County, three

in Harnett County and one in Johnston County

FERN’s report on plant outbreaks said that pork

plants specifically led in the number of cases

with nearly 6,000 cases as of May 19, followed

by beef and chicken nationwide.

Burke County

The ZIP code of Morganton that contains the Case

Farms poultry plant carries 550 of the entire

county’s 700 cases. Cases shot up after testing

of the poultry workers in early June,

reported The Morganton News Herald.

The plant and the Burke health department has

said they will not release those numbers.

“We are not identifying numbers at any

businesses since these cases are community

spread and it is all over the county,” the

public information officer for Burke County told

The Morganton News Herald this week. “It does

not provide any value to list all the businesses

that have positive cases.”

Case Farms told The N&O previously that they

were contact with the county health department

regarding the outbreak.

Lee County

The Pilgrim’s Pride poultry plant in Sanford has

had an outbreak since early April. Both the

county health department and the plant company

told The N&O they would not disclose case

numbers, though the county organized testing for

the workers.

Cases in the ZIP code of the plant and in an

adjacent ZIP code have tripled since May 1.

Pilgrim’s Pride parent company JBS had the

second-highest cases in its plants across the

nation, according to FERN.

A plant worker who resided in Chatham County died

from COVID-19 complications last

month and also infected his family, The N&O

reported.

Duplin County

The Butterball and Villari Foods plants in

Duplin both have outbreaks. Local TV station

WITN reported in April that Butterball had over

50 cases. Southerly

Magazine reported that

its Latino immigrant workers complained about a

lack of protections there and spread the virus

to their families.

Cases in the zip code of the Butterball plant

tripled to 304 since May 1, but at least 56 of

these cases are attributed to an outbreak at the

two nursing homes, according to NCDHHS.

Wilkes County

Nationally, Tyson Foods has the highest number

of coronavirus cases associated with a poultry

company. They announced that 570 workers tested

positive at its plant

in Wilkesboro last

month, the largest known plant outbreak in the

state. The outbreak shut the plant down

temporarily and infected workers from other

counties — the total cases in the county are

511, less than the plant outbreak.

Coronavirus cases in the two Wilkesboro zip

codes skyrocketed by roughly 1000% since May 1.

Wayne County

Two Wayne County ZIP codes weren’t included in

the average rate of increase because accurate

data before May 20 were not available. Virus

cases in the Neuse Correctional Facility in

Wayne County were being included in two county

zip codes until it was moved to a unique zip

code by NCDHHS.

At least 12 cases in one Wayne ZIP code are from

a nursing home.

Cases have grown in the ZIP codes of Case

Farms’s Wayne County plant — from 12 to 173 —

and also in the town of Goldsboro, a populous

area 20 miles away from the Butterball facility

in Mount Olive, which is split between Wayne and

Duplin counties.

Despite the national outbreaks at these

facilities, the U.S. Department of Agriculture

said in a statement June 9 that meatpacking

facilities are currently operating at over 95%

capacity during the pandemic compared to last

year.

The statement says that Secretary Sonny Perdue

“applauded the safe reopening of critical

infrastructure meatpacking facilities across the

United States.”

Declared a critical industry during the

pandemic, food processing plants have been

ordered to remain open under the Defense

Production Act by a presidential executive

order.

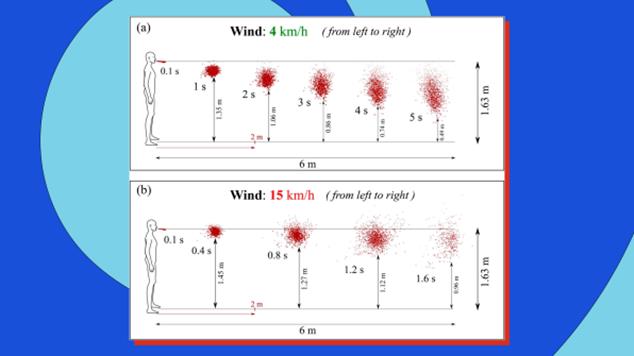

Social Distancing is not a Safe Solution

The conventional wisdom is

that 6

feet of social distance creates a safe buffer,

and restaurants, offices, and

even Starbucks cafes are being redesigned around

that tenet. Social distance does help prevent

transmission, but according to new modeling,

even a small breeze can spread COVID-19 up to 20

feet.

[Image:

Talib Dbouka/Dimitris Drikakis/AIP]

[Image:

Talib Dbouka/Dimitris Drikakis/AIP]

Dimitris Drikakis, the professor at University

of Nicosia, Cyprus, who created the model,

insists that this finding doesn’t mean that

someone coughing 20 feet away will get you

instantly sick. The overall amount of virus you

breathe in overtime matters, too. But his

research does confirm that even outdoors,

distance gatherings come with some risk.

On cruise ships and in many buildings, HVAC

systems use lower-quality air filters, which

might catch just 20% to 40% of viruses passing

through. On the tragic Diamond Princess cruise

ship, which quarantined thousands of passengers

to their rooms for nearly a month while the ship

was dry-docked in Tokyo Bay, air circulated

between cabins without HEPA filtering, infecting

700 people and killing eight people who were

breathing the same old stew of air.

In Fast Company Mark Wilson reports

that

U.S. office buildings may begin to retrofit with

higher-end HVAC systems (with HEPA filters and

even UV light sterilization hiding in the

ducts), which are more common in China, but it’s

hard to quantify how many companies and

landlords are actually taking those steps.

The safest option for quarantining viruses in

the air are negative pressure rooms, which

operate like vacuum cleaners, ensuring that no

pathogens can escape. But they’re designed for

hospitals. They’re not feasible for hotels,

offices, and other buildings for a variety of

reasons—including expense, the difficulty in

validating their design, and the fact that every

office worker in America would need their own

office with a door that is always closed. Only

2% to 4% of all hospital rooms are equipped to

be negative pressure spaces as it is.

Some scientists believe that summer could help

curtail the spread of COVID-19 due to heat.

Indeed, researchers have shown that extreme heat

can kill the virus; Ford even retrofitted police

cruisers to sterilize car cabins with nothing

but the hot air blowing in from the engine.

One component of air quality that hasn’t gotten

as much attention is humidity. Stephanie Taylor,

infection control consultant at Harvard Medical

School, is petitioning alongside companies that

make sensors and humidifiers to improve air

quality, for the CDC and WHO to adopt guidelines

around safe humidity levels—specifically that

indoor humidity should be kept between 40% to

60% (the current recommendation of the EPA).

That’s the range of what most people consider

comfortable humidity indoors, with air that

won’t dry out your nose. (By comparison, the

Mohave Desert ranges from 10% to 30% humidity.)

Taylor’s own interest in humidity began in 2013

when she was studying how infections spread at a

new hospital. Her research isolated just about

every aspect of a hospital you could imagine,

and she discovered a link between infection

rates and humidity in patient rooms. In fact, it

was the single biggest correlation she found. “I

was totally blown away,” Taylor says. “And to

tell you the truth, I was skeptical.”

But Taylor has since validated these findings on

studies at nursing homes and schools. And from

her research and others in the industry, she

identifies three ways that midrange humidity

levels stop the spread of airborne pathogens.

First, when air is too dry, large droplets don’t

fall to the ground as quickly as they normally

would. Instead, they dry out to become smaller

droplets, which float in the air longer (and

also take longer to drop to surfaces, meaning

the surfaces can continue to be contaminated).

Secondly, airborne viruses that thrive in

winter, like coronaviruses, simply aren’t as

infectious when they float through moister

air—whatever tools the viruses use to be

virulent are somehow stunted. “There are a few

theories as to why,” says Taylor. “But to tell

you the truth, I don’t think we fully understand

the mechanism.”

The final reason is that your respiratory immune

system just works better in greater humidity.

Recent research out of Yale exposed mice to a

strain of influenza. The mice were kept in the

same air temperature, but researchers tweaked

the humidity levels. They found that mice in

low-humidity chambers had a worse immune

response. Humidity didn’t actually remove the

influenza droplets from the air; instead, the

air moisture helped their bodies fight off the

virus better—all the way down to the cellular

level in their respiratory system.

Distancing. Filtering. Humidity. None of these

individual solutions can prevent the spread of

COVID-19. But used in combination, we can make

our indoor air safer—to make it through this

pandemic, sure, but also cold and flu season,

and whatever pandemic awaits us in the future.

“This type of infectious disease will come every

few years,” warned Chen, the Purdue

engineer, back in March. “I started doing

research when SARS broke out in 2004. Then

another time was the 2009 influenza from Mexico,

which killed 150,000 people around the globe.

Today we have coronavirus. Every couple of

years, this type of thing will come back.”

Mark Wilson is a senior writer at Fast Company

who has written about design, technology, and

culture for almost 15 years. His work has

appeared at Gizmodo, Kotaku, PopMech, PopSci,

Esquire, American Photo and Lucky Peach.

The full text is shown at

https://www.fastcompany.com/90515931/theres-a-key-way-to-curb-the-spread-of-covid-19-but-no-one-is-talking-about-it